Dalí Is Classical, Is Surrealist, Is

Pop Art!

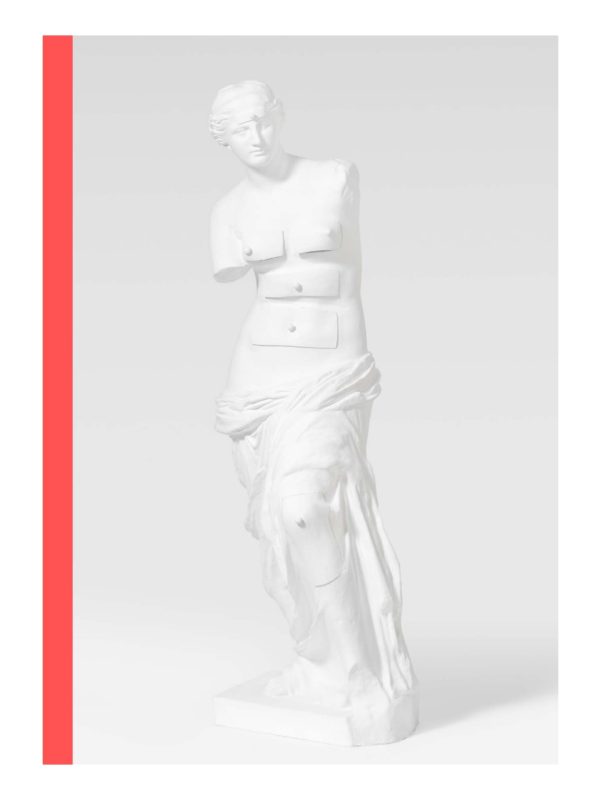

Discovered in 1820 on the Greek island of Melos, the Aphrodite or Venus de Milo is an icon that has been admired by generations of artists to the present day.

In 1936 Dalí “invented” his Venus de Milo with Drawers, a plaster sculpture which is now in the collection of The Art Institute de Chicago. With this daring work, he made the Hellenistic sculpture his own and turned it into a perfect blend of tradition and surrealism. And he did so transgressively, in a Daliesque way if one prefers, by sinking six drawers into the body of the goddess of beauty, love, and sensuality. They are drawers of enormous evocative and Freudian potential, with which Dalí invokes the subconscious and also, perhaps, the fears and contradictions of the modern human being.

Later, in 1964, he decided to make a limited edition of bronzes and reserved one, identified as ‘Exemplaire Gala Dalí’, for his Theatre-Museum. This is the only example that is not shown with the pompoms that are visible today on the plaster work of 1936 and also the bronzes of 1964. With this gesture, Dalí might have wanted to distinguish this sculpture from the other casts of the Venus de Milo with Drawers which are conserved in other places.

Later, in the 1960s, Dalí validated his Venus de Milo with Drawers as one of the forerunners of Pop Art.

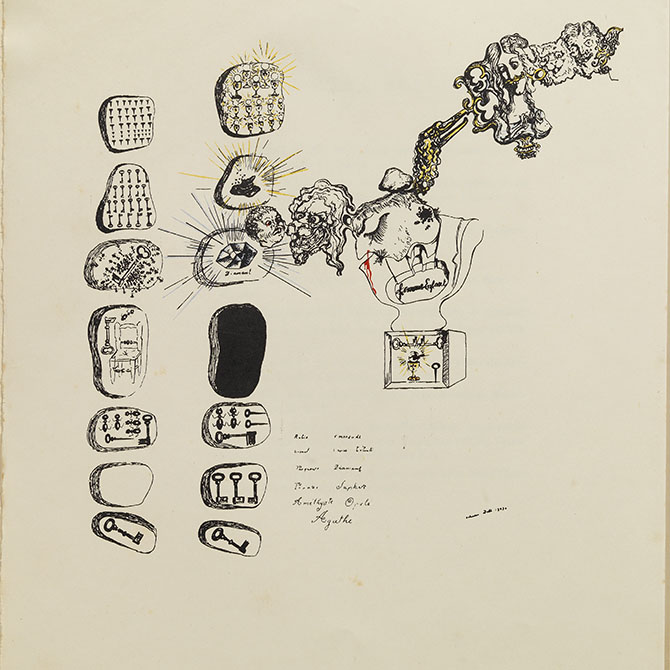

Drawers and keys, elements of transgression

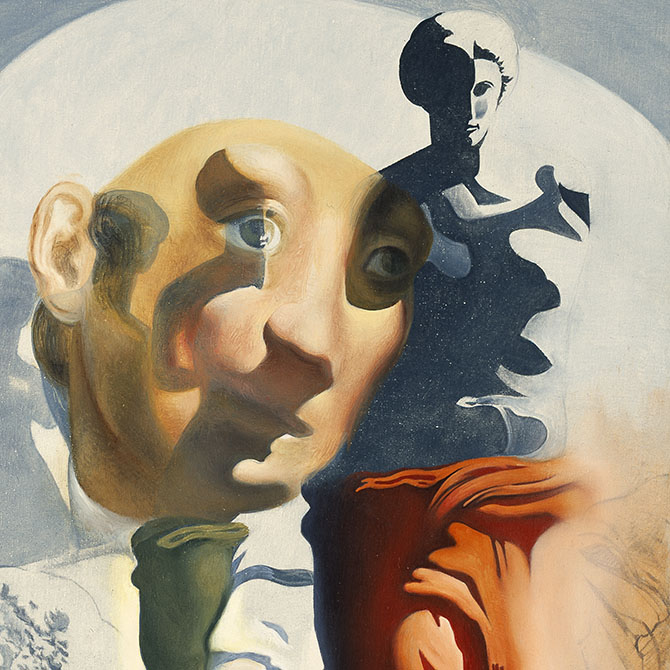

Both drawers and keys form part of Dalí’s most genuine and transgressive iconography. Drawers appear in his paintings after 1934, penetrating the bodies of some figures in works like Invisible Harp and Singularities. And they multiply throughout 1936, the year in which he created the Venus de Milo with Drawers. As for keys, they had already begun to appear in his first surrealist paintings, as demonstrated in the details of The Memory of the Woman-Child of 1929.

According to Dalí, ‘the only difference between immortal Greece and the contemporary era is Sigmund Freud who discovered that the human body, which was purely neoplatonic in the time of the Greeks, is now full of secret drawers that only psychoanalysis can reveal.’ In this regard, could these keys be understood as a metaphor for the psychoanalysis that would make it possible to reveal the images of Dalí’s concrete irrationality?

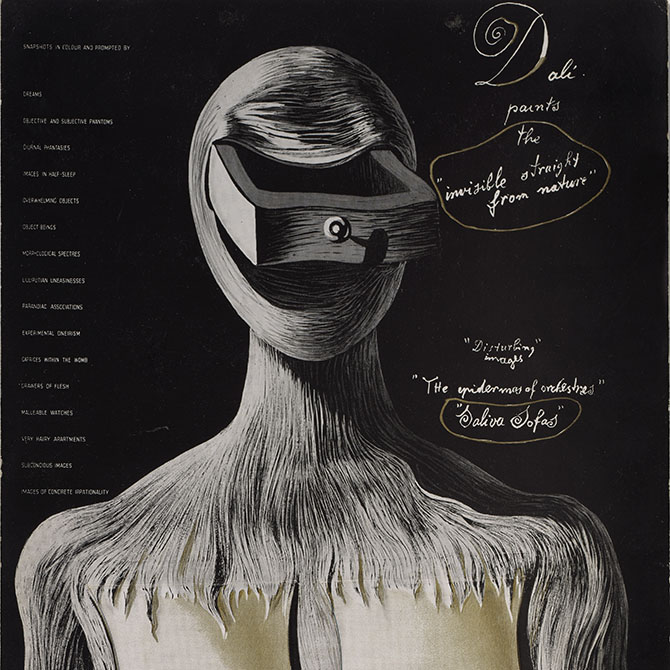

Dalí and the Venus in New York, 1939

New York was the setting for the presentation to the general public of the Venus de Milo with Drawers. In Dalí’s exhibition at the Julien Levy Gallery, this sculpture was part of an installation presided over by the reproductions of the Trylon and the Perisphere, the modernistic structures that were symbols of the 1939 New York World’s Fair. Here, hanging from the goddess’s neck and also depicted in the general decoration of the installation, keys are given a special emphasis.

It seems that the elongated pyramid representing the Trylon also showed Freud’s name, according to the press of the day. This evocation of the father of psychoanalysis, whom Dalí had met in person the previous year, would lead us to speak of the connection that has been established between his inquiry into the subconscious and the Venus de Milo with Drawers.

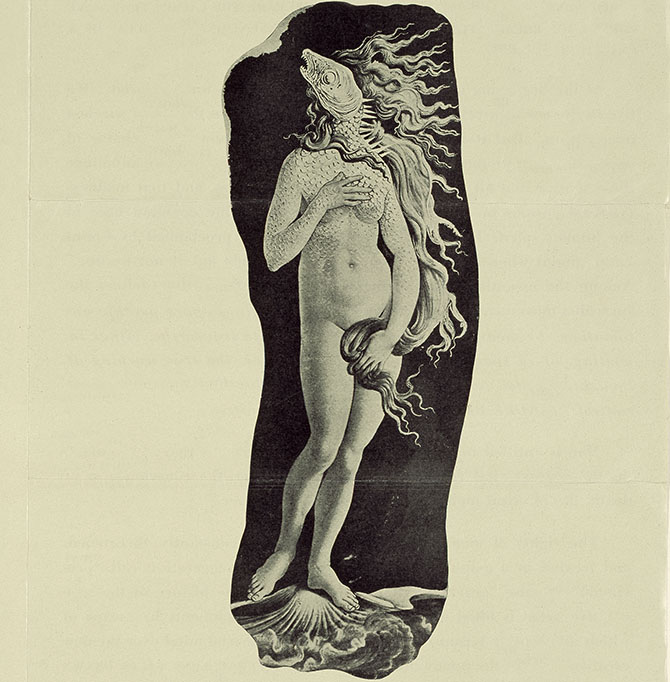

An Aphrodite with a fish head for the “Dream of Venus”, 1939

Dream of Venus was the pavilion designed by Dalí for the 1939 New York World’s Fair, a construction that also offered a prefigurative glimpse of what was to be the Dalí Theatre-Museum. Dalí conceived a large fish-headed Aphrodite—inspired by Botticelli’s version of the Greek goddess—to preside over the main façade. However, the organising committee censored his totally transgressive creation. Faced with this situation, Dalí spoke out for the artist’s creative rights in his manifesto titled Declaration of the Independence of the Imagination and the Rights of Man to His Own Madness:

‘Had there been similar committees in Immortal Greece, fantasy would have been banned and, what is worse, the Greeks would never have created their sensational and truculently Surrealist mythology, in which, if it is true that there exists no woman with the head of a fish (as far as I know) there figures indisputably a Minotaur bearing the terribly realistic head of a bull.’

Venus Is Classical, Is Surrealist, Is Pop Art!

In November 1964, Dalí announced before the cameras of Spanish television an installation of six Venus de Milo with their respective drawers on a balcony of his future museum. He imagined this project as ‘the most shocking of what is now called Pop Art’. Although the idea did not come to fruition, his announcement was a clear statement of intention.

Moreover, in Autoportrait mou de Salvador Dalí, a film directed by Jean-Christophe Averty and made in 1966, Dalí declared before the camera that his Venus de Milo with Drawers is ‘a lesson for Pop artists’. In his Prologue to Gaudí, the Visionary, published in French in 1969, he also even identifies his Venus as a forerunner of Pop Art.

Innovation: conservation and sustainability with a digital loan

A holografic creation made for this exhibition enables a dialogue between the Venus de Milo with Drawers of Chicago and the cast of the Dalí Theatre-Museum. Two Venuses for two historical times in the same century. This hologram uses the innovative emerging T-OLED technology. The video has been produced with 72 high-resolution photographs in which the 360º animation is digitally introduced.

With this digital loan, the Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí expresses its commitment not only to the use of technological resources in the domain of exhibitions, but also to the sustainability of international loans and the preservation and conservation of original works of art.

TRANSGRESSIONS

Digital Publication:

Transgressing Venus

Texts by Montse Aguer, Laura Bartolomé, and Jennifer Cohen

Download the publication